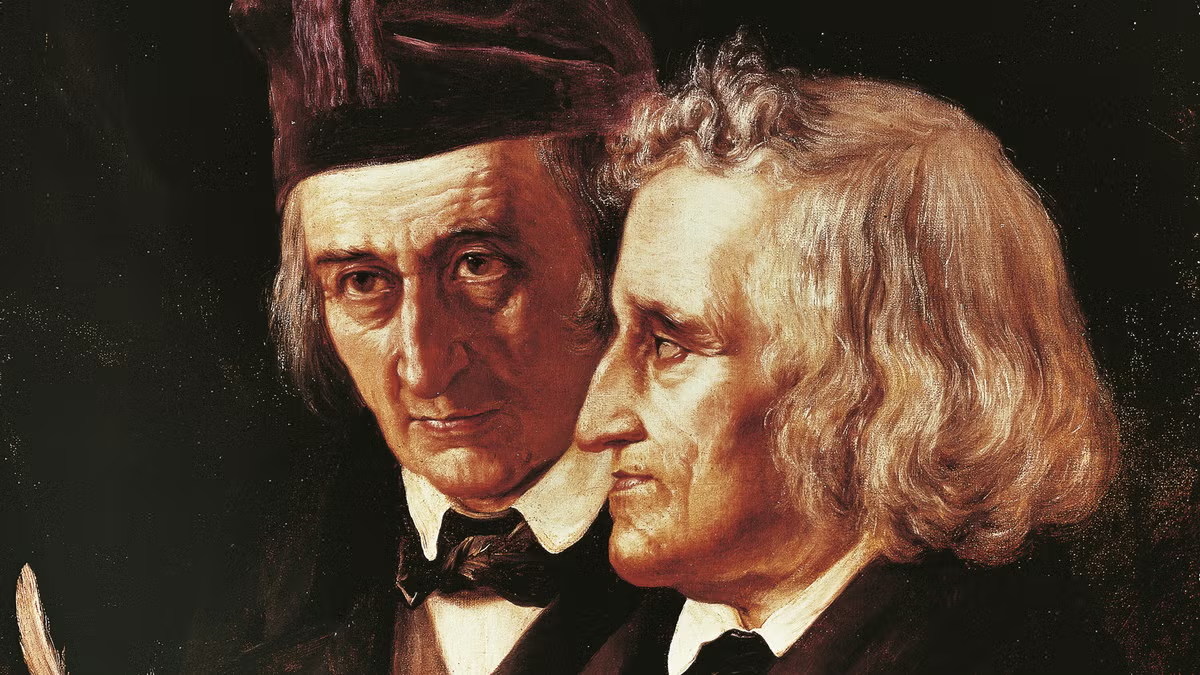

The Brothers Grimm are synonymous with folklore; writing in the 1800s, and seeking to unify the very disjointed 200-odd German provinces, they collected the stories of the Volk, the Folk (and yes, a Volkswagon is a wagon for folks). Some of these had been published earlier – for instance, French author Charles Perrault had written Histoires ou contes du temps passé (Stories or Tales from Past Times) in 1697, a work which included “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge” (“Little Red Riding Hood”), “Cendrillon” (“Cinderella”), “Le Maître chat ou le Chat botté” (“Puss in Boots”), “La Belle au bois dormant” (“Sleeping Beauty”), and “Barbe Bleue” (“Bluebeard”). However, there were still hundreds of unpublished, orally transmitted tales. The Grimms, Jacob and Wilhelm, set about putting them to pen, in part to foster a sense of national identity.

It’s hard to talk about national identity and Germany without getting into the fruition of such concepts; and as such, the Nazi’s were keen to use the Grimm’s work as part of their ideological propaganda, much in the same way that they absorbed Nietzsche and Wagner (Nietzsche was an unwilling participant (Wagner not so much)). However, that isn’t the point of this post.

Oral transmission is the way our stories have been passed down, to this very day. What is a Youtube influencer if not an oral transmitter? It took me years to read the Ramyana, because I knew it (or I thought I did) because my dad would tell me stories before bedtime. In the end, reading takes work; listening is much easier.

So this begs the question – who were the Grimms listening to?

Women.

At this point, I’m going to give a shout out to a book I haven’t accessed yet – but I believe fleshes this argument out. The work in question: Clever Maids: The Secret History of the Grimm Fairy Tales by Dr Valerie Paradiž. I think the title says it all.

A brief recap of tales they received from women:

‘Aschenputtel’, ‘Little Red Cap’, ‘The Robber Bridegroom’, ‘Briar Rose’, ‘The Worn-Out Dancing Shoes’, ‘The Bremen Town Musicians‘, ‘The Goose Girl’, ‘Hans My Hedgehog’ and ‘The Lazy Spinner’ are just a few examples of they stories they gathered from the women around them.

But of all the women who told them tales, the most important – in fact truly the Sister Grimm – was Henriette Dorothea Wild, known familiarly as Dortchen. Dortchen grew up next door to the Grimms, and would eventually marry Wilhelm. Nearly a quarter of the first edition of the Grimm’s fairy tales came from her. This body of stories included ‘Rumpelstiltskin,’ ‘Six Swans,’ ‘The Frog King,’ ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker,’ ‘Sweetheart Roland,’ ‘Mother Holle,’ ‘The Three Little Men in the Wood,’ ‘The Singing Bone,’ ‘All-Kinds-of-Fur,’ and ‘The Singing, Springing Lark,’; scholars believe she was also the most likely source for ‘Hansel and Gretel.’

And so yes – we are culturally indebted to Brother’s Grimm for writing down these tales. But in examining the Grimms, and the fact they have become folk legends in and of themselves, it’s probably worth the time to take a step back and examine where they got their Mojo:

They were transcribing the lyrics of their mothers, their sisters, their wives.

They were putting to ink the songs of Dorthcen.

And that, dear readers, is the Take Away. That, and take a moment to listen. You never know what you just might hear…

Discover more from Myth Crafts

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Wild Girl by Kate Forsyth is a beautifully told story based on the relationship between Wilhelm Grimm and Dortchen Wild. Definitely worth a read, and like well researched historical fiction, it reminds us of the context of the story telling that translated into well known tales.